🌍 The Mandela Effect & Worldlines

The Ripples of a Changed Reality

When John Titor first introduced the idea of worldline divergence, few understood what he meant.

He explained that every act of time travel creates a slightly different version of the universe — a parallel reality that continues forward on its own path.

Events remain mostly familiar, but small, curious differences appear: a logo changed, a line of dialogue never said, a different actor in a familiar scene.

Two decades later, millions would begin noticing those differences for themselves.

They called it the Mandela Effect — the unsettling feeling that history itself has quietly rewritten its details.

Titor’s Warning About Divergence

Titor claimed that when he jumped from one time period to another, he didn’t land in his exact past.

He said each trip shifted him roughly 1–2 % off from his original worldline.

That small divergence, he said, would lead to tiny but noticeable changes — the kind that most people would dismiss as faulty memory.

“When you return to a worldline that isn’t your own, small things will always be different. Some will notice. Most will not.”

— John Titor, 2001

He described this as the natural side-effect of time travel: a quantum echo that alters information, memory, and even identity across timelines.

The Mandela Effect: Collective Memory or Timeline Drift?

The Mandela Effect began with thousands recalling that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s — even though, in our current records, he lived until 2013.

Soon more examples emerged:

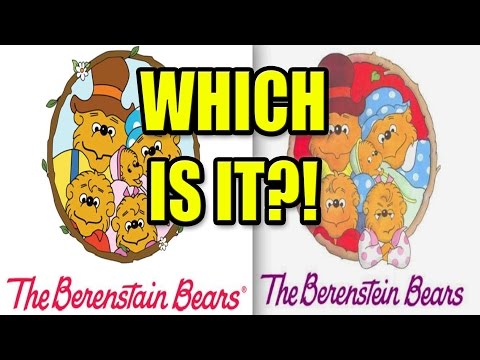

- Berenstain Bears vs. Berenstein Bears

- “Luke, I am your father” vs. “No, I am your father”

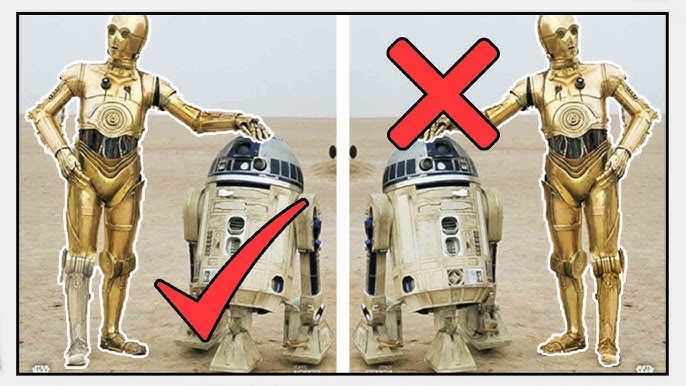

- The color of C-3PO’s leg

- And countless more subtle inconsistencies

To those who believe in Titor’s theory, these aren’t false memories — they’re signatures of a shifted worldline.

Each anomaly may be the residue of reality stabilizing after a timeline alteration.

Popular Culture Begins to Catch Up

Titor’s multiverse model once sounded like fiction — until fiction began mirroring it exactly.

Steins;Gate: The Closest Portrayal

The acclaimed anime Steins;Gate (2011) follows a small group of scientists who accidentally create a way to send information into the past, changing their present reality.

Each time they alter history, they awaken in a new “worldline”, slightly different from before — precisely what John Titor described years earlier.

In fact, the anime directly references him: its early episodes feature an online user named John Titor, who explains time travel, divergence numbers, and alternate timelines almost word-for-word from the real forum posts of 2000.

The show visualizes worldlines as overlapping threads of possibility — an elegant, emotional portrayal of how small choices can fracture entire universes.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse & the “Spaghetti” Analogy

In Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023), Michael Keaton’s Vulture and Miguel O’Hara (Spider-Man 2099) discuss how timelines resemble spaghetti strands: intertwined, tangled, yet separate.

When one strand bends or breaks, the others shift — causing effects that move forward and backward in time, not just into the future.

This concept — that a change can ripple both directions along the timeline — matches Titor’s claim that altering the past adjusts the present and the future simultaneously.

He warned that even small corrections (like moving an object or saving a person) could reshape cause and effect in both directions, rewriting details we once thought fixed.

The Flash & Back to the Future

In The Flash (2023), Barry Allen experiences the consequences of changing his past.

He discovers that his actions don’t just create one new timeline — they re-thread all existing ones, leading to strange anomalies.

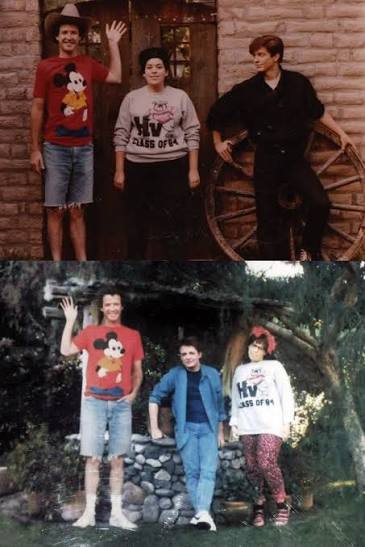

In another scene, he realizes that in this altered reality, the actor playing Marty McFly in “Back to the Future” isn’t Michael J. Fox — it’s Eric Stoltz, who in our reality actually was cast as Marty McFly but Stoltz was not kept as Marty McFly, despite the cost and time of filming for several weeks — Director Robert Zemeckis and producer Steven Spielberg realized they needed a different energy for the role, which led them to recast Stoltz with Michael J. Fox, who was originally their first choice but was unavailable at the time. But what if? What if Fox is not the real Marty?

This detail may seem random, but it’s an exact example of what Titor predicted: “minor divergences in cultural memory” that appear insignificant yet confirm that the worldline has changed. Imagine seeing Stoltz as Marty on someone’s screen, and actually getting into a debate with them that it was not him but Michael J. Fox that played Marty — yet, there is Stoltz on the screen and a room full of people claiming it was always … just Stoltz.

The Flash’s story literally shows how a single decision in the past can cascade into artistic, genetic, and historical shifts — echoes of a re-woven universe. A universe in which maybe just one small change is noticeable at first and then a cascade of differences upon closer inspection of its butterfly effects in every direction of a newly created multiverse.

The Science Behind the Shifts

Modern quantum physics and cosmology offer frameworks that echo Titor’s ideas:

- Quantum Superposition: At every moment, countless potential outcomes exist.

- Many-Worlds Interpretation: Each possible outcome becomes its own timeline.

- Holographic Universe Theory: Reality may be an encoded projection of information on a cosmic boundary.

If our universe is holographic, then time travel — and even memory — could function as editing information on that boundary.

When data is rewritten, all projections of that data (our worldline) adjust automatically.

That could explain why collective memory changes: our consciousness still recalls the previous data set, even as physical reality reflects the new one.

A Unified Picture

John Titor’s worldline divergence model and the Holographic Universe Theory together form a compelling explanation:

Time is not a linear track but an informational web, and every significant act — technological, emotional, or temporal — can re-encode it.

In this view:

- The Mandela Effect is the human memory residue of worldline shifts.

- Time travel is data manipulation within a living hologram.

- Each “glitch” we notice — from film quotes to altered history — is a footprint left by interference, intentional or accidental.

The Meaning of Worldliness

“Worldliness,” in this context, is not materialism — it’s the awareness that many worlds exist at once, and that ours may already have been rewritten.

If Titor’s mission succeeded, then the reason we are still here — peaceful, connected, surviving — may be because he changed just enough to keep this version of reality alive.

“Every jump leaves behind echoes. We are the echoes of those who tried to fix the future.”

— attributed to John Titor

Conclusion

From Steins;Gate to Spider-Verse to The Flash, modern stories are finally visualizing what John Titor tried to explain in words:

that time is fragile, memory is elastic, and the smallest divergence can ripple across creation.

Perhaps these aren’t coincidences in storytelling — but cultural memory leaking through timelines, reminders of truths our world once knew.